I’m not sure how seriously I take this story, but it is interesting – attempting to measure something intangible. How certain are writers about what they say about God and ethics? And how open-minded do they think they are?

So I hope it’s worth a look.

Jonathon Haidt and moral reasoning

I have written previously about psychologist Jonathon Haidt, who believes that we make most political, ethical and religious judgments intuitively (by “gut feeling”), and then rationalise our reasons afterwards. Other decisions may be made more logically.

He quotes cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, who summarised their Argumentative Theory based on a large amount of research:

“The function of reasoning is argumentative. It is to devise and evaluate arguments intended to persuade…. Skilled arguers are not after the truth but after arguments supporting their views.”

Not everyone agrees with them, and I’m not sure if I do completely, but there is good evidence for what they say.

Critics reasoning about religion

Haidt had noticed that some so-called “new atheist” writers sounded angry, and wrote with what seemed like greater certainty about religion than he would as a scientist. So he wondered: “What kind of reasoning should we expect from people who hate religion and love reason?”

Haidt decided to investigate this question by considering books by three atheists with strong anti-religion views – Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett and Richard Dawkins. As a comparison, he also analysed books by three politically right wing writers who are not regarded as scientific and three scientists (including himself) who write about religion but are not anti-religious. Subsequently, he analysed a number of other books, 30 in all, to strengthen his initial analysis.

His idea was to test his hunch that anti-religious scientists wrote with greater certainty than other scientists, indicating that they were approaching the topic more argumentatively than with reason.

How it was done

Haidt used a text analysis program to count specific words and phrases that indicated certainty (e.g. always, never, no doubt) and expressed the total as a percentage of the total words in each book. This is admittedly a rough estimate as some of the words could be used to indicate views the writer didn’t agree with; nevertheless it gives an indication.

Later he did a second run using a stricter list of ‘certainty’ words.

Results of the analysis

The results tended to confirm his suspicions.

Initial nine books

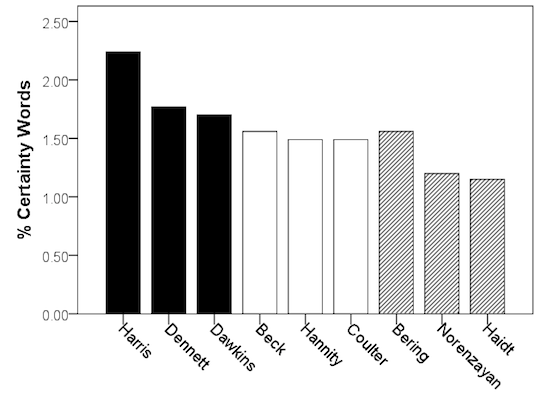

In the initial test of nine authors, the three ‘new atheists’ used more ‘certainty’ words (especially Sam Harris), the three more neutral scientists used the least, and the right wing commentators were in the middle.

Use of ‘certainty words’ – taken from Haidt, 2014.

The results for the more limited list of words gave similar results, though one right wing author (Beck) was now second highest.

Full set of 30 books

This list included many more general books as well as several books by some authors. The results were a little harder to classify but still generally similar:

- The highest average score for an author was for christian writer GK Chesterton (2.85), followed by Sam Harris (2.3), Martin Luther (2.26) and the inaugural speeches of US presidents (2.18).The lower end of the range were Norenzayan (1.21) and Haidt (1.25).

- Overall, the books by Dawkins and Dennett were in the top half of the list, the right wing authors were in the middle and more neutral scientists were in the lower half.

This very rough analysis suggests that the new atheist writings express certainty in a similar way to religious writers Chesterton and Luther, and very differently to other scientists writing on religion.

Sam Harris replies

Sam Harris has responded to Haidt’s analysis, pointing out how use of certain words doesn’t necessarily indicate state of mind, and giving an example where he was persuaded by reason to change his mind. He finishes with a clever paragraph using many of Haidt’s ‘certainty’ words.

Harris comes out of this sounding quite reasonable and open-minded. It seems to me that he tends to use stronger language even when not arguing. The change of mind example he gives suggests to me that he formed his initial opinion too quickly, argued it strongly, then reversed his view on the basis of one extra input.

Conclusion

I don’t think I’d want to pin too much on this simple analysis. But as Haidt says, it can confirm suspicions – in this case that Harris, Dennett and Dawkins don’t appear to write objectively about religion, but argue beyond reason to support opinions they already hold. Not much of a surprise there – it’s something we all do when we talk about religion and ethics. But it suggests their writings should be categorised as ‘religion’ rather than ‘science’. It also throws light on two other authors who claim great certainty for themselves.

Read more

- Christians vs atheists: what type of person do you want to be? and Rational thinking is over-rated? on this website.

- Jonathon Haidt’s two articles: Why Sam Harris is Unlikely to Change his Mind and The Righteous Mind Challenge

- Sam Harris’ response: The Pleasure of Changing My Mind

- Neurologist Robert Burton on certainty.

It’s never been a secret that we make most of our decisions, moral or otherwise, on the fly for instinctive or emotional reasons. Moral decisions are probably particularly prone to this as there are few metrics in moral reasoning. The trolly problem demonstrates this quite well.

As for making an argument in such a way as to betray your emotional commitment to it. The fact that you are emotionally committed doesn’t mean that your argument can’t be completely objective or at least as objective as the argument of a less committed person.

I don’t know. This piece seems almost designed to make it sound like Christians are more genuine in their arguments. It’s been my experience that both sides of the fence are guilty of the “I’m right you’re wrong” condition.

Hi Gordon, I don’t think Haidt and Mercier & Sperber are merely talking about “emotional commitment” in what may be an otherwise rational argument. They are saying that the deep basis of some types of belief is emotional and the rationalisation is post hoc. Whether they are correct is another question, but that is what they are saying (I think).

Hayden, it doesn’t say that at all. Haidt’s initial comparison was not about christians at all, but when he added in the extra texts, two religious writers (Chesterton and Luther) were up there with the atheist Harris as the highest scorers.

Both Haidt (I believe) and my post were making a quite different point – that both christians and anti-religion atheists are similarly likely to be influenced by both emotion and rationality.

@unkleE

Nevertheless, I find it difficult to see how this particular analysis could tell the difference between a position held for rational reasons but with emotional commitment and a position held purely because of emotional commitment.

If I make a strong case for long sentences for paedophiles. If this case is logical and my argument quotes statistics on recidivism and other telling data I don’t see how the the process used in this analysis is going to say anything at all about the strength and rationality of my case just because I use phraseology which shows I feel strongly about the subject.

Hi Gordon, I’m not sure how much of Haidt’s writing you have read, but I think he is saying something different to what you express here.

On the basis of a large body of research, Haidt has concluded (rightly or wrongly) that we generally make decisions on intangibles like ethics, politics and religion intuitively, and then use reason to justify that decision. That doesn’t make the decision wrong, it just describes the process he believes generally occurs.

With that understanding, he looks at the writings of those who use a lot of certainty words about God, more than those who have a scientific (and hence impersonal) approach to religious belief (because they are studying it rather than deciding whether to believe it or not) and finds they tend to be either christian believers or anti-christian atheists. From this he draws the tentative conclusion that both groups are deciding on the basis of intuition rather than rationality.

But note this study doesn’t demonstrate the broad conclusion. That comes from the body of research. This little exercise is built on that body of research.

@unkleE

I have to say that I am deeply unimpressed by your last post. I have not criticized the thrust of Haidt’s general findings which I agree with. I have criticized the efficacy of a crude research method to determine who has a truly rational basis for their arguments. You have not answered this criticism at all. It is clearly a fallacy to assume that someone who uses “phrases of certainty” showing an emotional commitment automatically lacks a rational basis for that commitment. Please address the question if you can.

Gordon, you keep assuming what I don’t think, and I don’t think Haidt thinks.

You say: “I have criticized the efficacy of a crude research method to determine who has a truly rational basis for their arguments” But I don’t think this clearly crude research method determines anything. I think it is an interesting though uncertain illustration of something he regards as determined from other research.

As for “It is clearly a fallacy to assume that someone who uses “phrases of certainty” showing an emotional commitment automatically lacks a rational basis for that commitment”, I don’t think he says anyone lacks a rational basis, Haidt just says the intuitive comes before the rational. If you want to question that, you’d have to critique the large body of research that Haidt believes establishes this, not look at this little exercise.

@unkleE

I’m afraid now you are obfuscating. This analysis method does not show that rationalising comes after intuitive commitment. It merely shows emotional commitment. This is the whole point of my comment. This crude method does not detect the situation where the logical reasons for something are the reason the belief exists in the first place but the holder of the belief has become emotionally attached to it some time after his reasoned acceptance of the belief. And, most importantly, this method does not discriminate between well founded ideas and ideas without sufficiently adequate evidence.

Most importantly, although you may not agree, secular beliefs about reality are more likely to be founded on empirical data backed up by rational argument compared to religious beliefs where there is a dearth of strong empirical evidence.

That means that this already unsatisfactory method is more likely to produce fallacious claims about the motivation of secular individuals than religious individuals and fallacious implications about the validity of their beliefs.

Hi Gordon, twice already I have said that this “crude research” DOES NOT form the basis of Haidt’s conclusions about rational and intuitive thought, and now this is the third time you have criticised a view OPPOSITE to what I am saying. And now you say I am obfuscating. I think I have nothing more to say, thanks.

I was pleasantly surprised by Sam Harris’s change of mind, especially as it only took one movie to change his mind (not exactly the best of evidence, but let’s not be harsh now).

Note that I think it is better to agree with his ‘enemies’ on most matters on which they disagree (typically foreign policy), so I don’t think I am biased to agree with him here.

Hi IN, glad to see you around!