The Turin shroud is a famous piece of cloth which is claimed to have been Jesus’ burial cloth, and contains an image of him. Sceptics say it is a medieval fake.

Is there any way to decide who is right?

Declaration of personal interest

I am a christian who believes in the resurrection of Jesus. Thus the proposition that the Turin shroud was Jesus’ burial cloth, and that it might have been affected by his resurrection, is one I am able to believe if the evidence points that way.

On the other hand, I am not a Catholic. I think the interest of some Catholics in holy relics is somehow not in keeping with the life and teachings of the Jesus of history, and I am uncomfortable with some of the more extreme claims about relics.

I therefore come to the Turin shroud with a degree of scepticism, and with the impression that it has been shown to be a medieval artefact.

Facts about the shroud

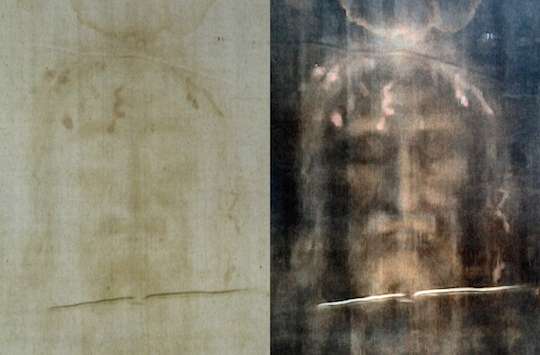

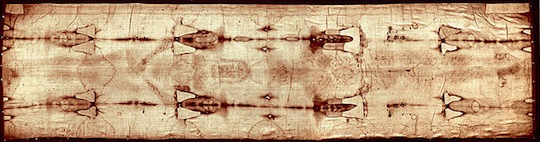

The shroud is a piece of linen cloth about 4.4m x 1.4m. It contains the front and back image of a man who appears to have been injured in the way the New Testament portrays Jesus was injured at his crucifixion. The image is more visible when viewed as a photographic negative.

The shroud is first known to have existed in 1355, and its whereabouts are known since that date. Before that, there are some possible references to it, especially if it is the same object as the Image of Edessa, another ancient shroud whose history is better known, but this is uncertain.

Many Catholics over many centuries have believed it is a holy relic, though the church is noncomital on this. Much scientific testing was done by the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP), a multidisciplinary group that operated from 1977 to 1981, and by numerous scientists since. STURP apparently contained sceptics as well as Jews and Christians, but is much maligned by sceptics.

Arguments in favour of the shroud’s authenticity

The arguments for the shroud’s authenticity form a cumulative case.

1. Features of the cloth look first century

- The shroud has an unusual seam that has only been seen in a first century cloth.

- It appears to have been cut from a larger piece, of a size made in Roman times but not in the Middle Ages.

- Vanillin is a compound found naturally in plants, including the flax used to make linen. After the plant is harvested and made into cloth, the vanillin slowly depletes. The shroud contains no vanillin, and one set of very approximate tests suggests it must have been made before 700 CE. However, as we will see, critics dispute the method and the date.

- Some experts claim to have found pollens on the shroud that originate in Palestine.

- Recent research, using infra red spectrometry, dated the shroud to between 280 BCE and 220 CE, much earlier than the dates obtained by disputed radiocarbon dating.

2. The image looks like a person crucified by the Romans

It is argued that the image must have been made by a body (certain features could not have been merely painted) and this person was nude and had recently been whipped, crucified, stabbed in the side , all things common in Roman executions.

3. Features that were uncommon, but true of Jesus

- The image shows wounds that look like the crown of thorns reported in the gospels, but unknown in any other Roman execution.

- Crucifixions generally involved common criminals, who would not normally have been wrapped in an expensive cloth like this.

- The body was only wrapped in the shroud for about 30 hours – if it had been longer, decaying processes would have begun, but these are not evident – which would be unusual, but fits with Jesus being resurrected after that time.

4. The image contains blood

Those supporting the shroud’s authenticity say tests indicate the shroud contains human blood (a claim contested by sceptics):

- The blood has soaked into the material, as you’d expect, whereas the image is only on the surface. If both were paint as claimed by sceptics, you’d expect them both to soak in the same amount.

- The chemicals you’d expect to find in the blood are found in the “blood” on the shroud. In particular, bilirubin, which is high in the blood of a person who has suffered extreme trauma, is found on the shroud.

- The serum from the blood on the shroud makes small rings around blood stains, visible in UV light but not visible to any painter in the Middle Ages.

- One researcher found evidence of vein and arterial blood in the right places, something not likely to have been known by medieval artists.

- Other researchers found evidence of DNA and even a blood group (AB – though old blood often has decayed to appear as AB).

5. The image is more like Jesus than medieval people knew

The image shows signs of a number of features of Jesus’ crucifixion that we understand today, but which were not understood in the Middle Ages.

- The nails were hammered into different parts of the body that usually depicted in Medieval times, but now known to be correct.

- The whip marks appear consistent with the use of a Roman flagrum by two different people. It is argued that the shape and pattern of wound left by these whips was not known in medieval times.

6. How was the image formed?

It wasn’t painted – the image is just on the surface, and hasn’t penetrated into the fibres as paint would have done – and it didn’t come from radiation.

While some sceptics have suggested ways the image might have been formed, it is claimed that no explanation is physically, chemically, biologically and medically sound, and no method has been proposed that was within the capabilities of medieval forgers.

One suggestion by shroud “believers” is a Maillard reaction. This occurs when soap herbs used in the manufacture of the lined form a thin layer on the surface of fibres, and then react with amino acids released from the body shortly after death, creating brown marks similar to what is seen on the shroud. But critics say the image is too high resolution for this.

The lack of a natural explanation has led some to claim the image was formed during a release of energy when Jesus was resurrected, but I have seen no real explanation of this process.

7. The Pray manuscript

A manuscript dated about 1192 contains a picture of an object that looks like the shroud and shows many minor details which are exact copies, suggesting the shroud was in existence more than a century before the generally accepted date, and earlier than sceptics believe it was made.

8. The Sudarium of Oviedo

There is another artefact, apparently a cloth that covered a dead man’s blood-stained face, reportedly removed from Palestine in the early seventh century. Similar arguments have been made for or against its identification as the cloth that covered Jesus’ face. Most interesting is the fact that blood marks on this cloth match those in the facial area in the shroud.

Since this cloth is almost certainly older than the sceptical dating of the shroud, it is arguably further evidence of the authenticity of the shroud.

Summary

It is argued that all these evidences show that the shroud once covered the body of a man crucified by the Romans in the Middle East around the first century, in a manner which makes it unlikely that it could have been anyone other than Jesus.

Arguments in favour of a medieval date

Sceptics contest many of these claims, but base their scepticism mainly on carbon dating.

1. Problems with the cloth

It is argued that some features of the cloth – it’s 3-1 herringbone pattern and the thread spun with a clockwise twist – don’t indicate a first century date. However it seems that these patterns are rare in any period.

2. Not all the claimed features are clear

Proponents have claimed that the image shows wounds from crucifixion, whipping, crown of thorns, coins on the eyes, the man was circumcised, etc, but not all these are as clear as claimed, and are open to interpretation.

3. Paint and no blood

Contrary to STURP, sceptics say that the image could have been painted (with the paint now worn off leaving only traces of impurities), and there are no traces of blood on the fabric, but rather iron oxide.

Experiments have shown that a plausible image can be produced by placing a cloth over a person and rubbing with pigment and then baking the cloth to simulate aging, although critics say the image is not really comparable, and it shows the image where the body was in contact with the cloth, whereas the shroud shows the image where there was no contact.

4. The accuracy of the image

- The proportions of the image are anatomically wrong, and don’t fit a man lying down with a shroud draped around him (such an image should be larger than a front-on view). However the proportions couldn’t be wrong if the image was produced by rubbing pigment over a person draped in the cloth.

- The hair appears to have been hanging down as if the man was standing rather than lying, and it isn’t caked with blood as you’d expect.

Supporters of authenticity have provided explanations of all these detailed problems.

5. Carbon 14 testing

The strongest evidence for medieval dating is a set of carbon 14 tests done at three separate laboratories. The original testing protocol was for two different types of tests at 7 laboratories on samples from different parts of the shroud, but a church official reduced this to one test at 3 laboratories on samples from one corner only.

The tests dated the shroud at between 1260 and 1390 CE. This time-frame matches the earliest documented “discoveries” of the cloth and coincides with a time period in which a lot of holy relics were being manufactured. If these test results are correct, obviously the shroud is medieval and can’t be genuine. This is the strongest argument against authenticity.

However shroud supporters present a number of arguments against these dates.

- Carbon 14 dating has been found to be in error in other artefacts from antiquity.

- The samples were taken from a corner of the cloth that had been repaired in the middle ages, and so were not measuring the age of the main part of the shroud.

- Vanillan tests confirm that the shroud is older than that, and that there are indeed two different linen fibres one medieval and one much older.

- Infra red spectrometry indicates a much earlier date.

The matter could be resolved by doing more complete radiocarbon testing, but so far the church has been unwilling to allow this.

6. It could be a person other than Jesus

There is no absolute identification with Jesus. However the crucifixion of Jesus is the only time there is any record of a crown of thorns being placed on a victim.

7. The shroud doesn’t prove Jesus’ resurrection

Even if the shroud was genuinely used to wrap Jesus’ body, it doesn’t prove Jesus was resurrected.

Some people have suggested that the image was formed by a burst of energy when Jesus was resurrected, but I have not seen any plausible explanation along these lines. Thus the shroud isn’t directly evidence of the resurrection, though if genuine, it would establish (against Jesus mythicists) that Jesus was a historical person who really was crucified.

How can a neutral person judge?

This is only a small summary of the evidence for and against the authenticity of the shroud. There are many, many peer-reviewed papers and internet articles.

How can an outsider sort through the information? With so many conflicting claims, who can we trust?

STURP and the ‘believers’?

Scientists who support the authenticity of the shroud have published many papers in peer-reviewed journals. These papers are presented in a sober fashion as befits such journals. However they are accused of having made their minds up in advance, presumably (though I don’t know) because most of them are believed to be Catholics.

I have no evidence of bias, but clearly they have a viewpoint that is no longer disinterested. This group’s evidence must be carefully considered, but an impartial person couldn’t take this evidence on its own.

The sceptics?

The sceptics too have their viewpoint, and there are good reasons why an impartial reader cannot accept this view without question either. They have published far less in peer-reviewed journals, all their arguments appear to have been answered by the ‘believers’, some of their writings make unscientific slurs against their opponents (Schafersman uses words like “pseudoscientific”, “hopelessly incompetent” and “unscientific, nonsense-mongering”) and they claim much greater certainty than their evidence merits, which suggests serious bias.

This group’s evidence must also be seriously considered, but an impartial person couldn’t take this evidence on its own either.

Atle Søvik

I was fortunate to come across a 2013 review of both sides of the argument by Atle Søvik, a Norwegian Philosopher of Religion and Professor of Theology. His review is based mainly on published peer-reviewed papers, and is found in a main paper and a supporting paper.

It may be thought that a Professor of Theology isn’t an impartial observer, but I believe this is the most balanced assessment I have come across, because he is an academic, he seems impartial and reliable, it is in a peer-reviewed journal, he is not Catholic and he is likely a liberal christian who isn’t as strongly biased towards supernatural explanations as a naturalist would be biased against them. I am strengthened in this conclusion after brief correspondence with a sceptical member of his review team.

Assessment

Using Søvik’s assessments as a base, but drawing my own conclusions, here is my assessment.

There is both good and poor methodology on both sides.

Sceptics point out several places where pro-shroud tests have used doubtful methods – for example:

- Vanillan testing was done using a qualitative method when a more precise method, and the equipment to perform it, were readily available.

- It would have been highly incompetent if the material to be radiocarbon dated was taken from a patch, and no-one recognised it.

- The analysis of the apparent blood and pigment was said to be incompetent.

However the sceptical analysis has likewise been criticised, with their chief expert (McCrone) accused of using old light microscopy instead of the more advanced electron microscope, and not making his methods more public. The sceptics have been accused of failing to answer many of the important pro-shroud evidence. I have also found the sceptics to be more emotional, derogatory and apparently prejudging the question than their opponents.

In the end, we have to trust expert peer-reviewed science on both sides, and be wary of non peer-reviewed papers by less experienced researchers.

The weight of evidence

The pro-authenticity group seems to have produced far more evidence and analysis, and more peer-reviewed papers, than the sceptics. This is understandable, for they are likely more motivated (e.g. they have set up conferences, groups and websites in support of their views), but it means sceptics tend to rely on the same few expert opinions while their opponents have much more ammunition. The challenge for an independent reviewer is to be influenced by quality, not quantity!

There is blood on the shroud.

This is much argued, but Søvik goes through all the arguments in detail (16 pages) in his Excursus, and gives many reasons for believing that the experts who identified blood were more thorough and comprehensive than those who say it is only paint. The pro-shroud experts have answered all the sceptical arguments and provided many competent papers to support their conclusions, whereas the sceptics have left many pro arguments unaddressed and have only one older paper in their support.

The image is not painted.

Most of those who believe the shroud is authentic, and some sceptics too, agree that the image cannot have been painted on.

No-one has satisfactorily shown how the shroud’s image was produced.

No-one, on either side, can explain and demonstrate how the image was formed. The reconstruction by Garlaschelli in 2009 is the best attempt so far, but lacks many of the important features of the shroud. The hypothesis of a Maillard reaction merits further consideration. Some believers postulate that the image was formed when Jesus was resurrected, but I have seen no scientific way to test this idea.

The radiocarbon dating is the only strong argument for a medieval date.

If those tests were correct, the argument is over. However sufficient doubt has been raised to warrant caution, especially in the light of the earlier dating obtained by infra red spectrometry. On the other hand, if the corner where the tests were done has been patched, it ought to be easy to verify this, yet I haven’t seen that verification.

The radiocarbon tests need to be re-done. But in the meantime, the existing results make it impossible to confidently affirm a first century date.

The vanillin testing was inadequate to draw safe conclusions.

The vanillan testing suggests an early date and supports doubts about the radiocarbon dating, but the results are not as reliable as would be needed to overturn the radiocarbon dating.

It may be evidence for Jesus, but not for the resurrection.

If the shroud is found to be first century, then it seems quite possible that it was the one used on Jesus. The crown of thorns, and the much higher motivation to preserve this cloth than any other seem to point to this.

However there seems to be no clear connection to the resurrection. The claim that the image was formed miraculously is untestable. Thus the shroud, if genuine, doesn’t appear to “prove” the resurrection as some sceptics seems to fear, but the lack of any well established natural explanation for the image means it will remain an arguing point.

My conclusion

It seems to be a case of the carbon dating vs the rest of the evidence. Søvik cautiously concludes that the evidence for a first century date is slightly stronger, but I think neither side has proved their case or shown the other side to be wrong. The sceptical case relies on a few old papers and a lot of bluster, but the case for authenticity stumbles on the radiocarbon dating. I don’t think we can be confident either way. (I’m sorry to have to sit on the fence.)

I must admit I feel a little sceptical, not based on the evidence, but from an innate doubt that God would work in this way – after all, Jesus refused to use spectacular signs to authenticate himself. I cannot remove from my mind the many other relics, some of which are quite impossible, and some of which (e.g. non-decaying saints) seem quite superstitious.

If only the radiocarbon and vanillin testing could be re-done by agreed best methods, we might get a better answer. In the meantime, both believers and sceptics would do well to avoid making over-strong claims.

References

Neutral references

- Wikipedia on the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo.

- Atle Sovik: The Shroud of Turin – A Critical Assessment and Excursuses to the Article “The Shroud of Turin – A Critical Assessment”

- Examine the shroud for yourself with Shroud Scope.

- A christian reviewer who comes to a similar conclusion to me: Probing the Shroud of Turin (Michael Gleghorn)

Pro-authenticity references

- Thibault Heimburger: A Detailed Critical Review of the Chemical Studies on the Turin Shroud: Facts and Interpretations and Comments about the Recent Experiment of Professor Luigi Garlaschelli

- Dating: Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of Turin (Raymond N. Rogers), Textile Evidence Supports Skewed Radiocarbon Date of Shroud of Turin (M. Sue Benford and Joseph G. Marino) and alternative infra red spectrometry dating.

- Blood on the shroud: Blood on the Shroud of Turin: An Immunological Review (Kelly P. Kearse) and critique of Walter McCrone (‘Shroud University’).

- Radiation From the Shroud of Turin a Clue to Jesus’ Resurrection?

- A Summary of STURP’s Conclusions

- The Sudarium of Oviedo: Its History and Relationship to the Shroud of Turin (Mark Guscin)

- Shroud of Turin website: Home page and Debunking The Shroud: Made by Human Hands (I’ve listed this as pro-authenticity, although this page has both viewpoints).

Sceptical references

- Charles Freeman: The Origins of the Shroud of Turin

- Responses to Ray Rogers article on : A Skeptical Response to Studies on the Radiocarbon Sample from the Shroud of Turin by Raymond N. Rogers (Steven D. Schafersman) and Critique of Rogers’ so-called vanillin clock for dating the Shroud: why was Stanley T. Kosiewicz not a co-author (and where’s the data)? (Colin Berry).

- Walter McCrone: The Shroud of Turin: Blood or Artist’s Pigment?, summary article and update.

- The Shroud of Turin: Burial cloth of Jesus or cheap fake?

- 2009 reconstruction: New Shroud of Turin Evidence: A Closer Look (Live Science), Scientist re-creates Turin Shroud to show it’s fake (CNN).

Main picture: Turin shroud positive and negative displaying original color information 708 x 465 pixels 94 KB” by Dianelos Georgoudis – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Smaller picture from Wikipedia.

Interesting, although I do tend to think of the shroud as irrelevant to the question of the truth of Christianity. However, I don’t agree with the statement that Jesus refused to use spectacular signs to authenticate himself. I think that is precisely what he did. Raising Lazarus was pretty spectacular, and he did use his miracles as a reason for people to believe him.

Hi Phil, yes I don’t see the shroud as an evidence of christianity. But A knowledgable Catholic on blog made a strong case, and I thought it was worth checking out.

My statement about Jesus not using spectacular signs was based on the temptations. I also note that on many occasions he told people he healed not to publicise their healing widely. Yes, raising Lazarus was spectacular, but he didn’t do it in a showy way, and the story only appeared in John’s gospel, not in the synoptics (some say it wasn’t safe for the family to have advertised the story earlier).

All that for someone who possibly didn’t even exist. Hilarious to say the least!

Hi Stick3, glad you got some enjoyment out of it!

…. but does ‘Stick3’ exist? I suspect a robot that is trying to pass the Turin(g) test. LoL

🙂

Hi UnkleE,

I stopped by your blog today and I’m reading through some of your recent posts. I wanted to say that I think you did a very nice job on this post covering a lot of points in an overall summary. After I spent two weeks reading everything I could find on this subject and watching a lot of the shroud videos on YouTube my conclusion matched yours exactly: Another round of carbon dating should be performed, probably using several different areas from the cloth. Until such time I will remain on the fence as you are.

There is one minor detail I would add to the skeptical side:

– The time-frame of the carbon dating matches the earliest documented “discoveries” of the cloth and coincides with a time period in which a lot of holy relics were being manufactured.

Hi Dave, I’m glad you found this. When we discussed previously on Nate’s blog, I said I’d do some work on this when I had time, and if I’d seen you back there I’d have mentioned it. But I didn’t see you.

I didn’t watch any videos, but the Søvik paper was my goldmine for it gave me links to so much else. I was fortunate that a Norwegian internet friend was one of the reviewers, and he found me a translation.

I think your additional comment is fair, and I will add it in, thanks.

I think the interesting thing about the previous discussion was how black and white it all was – Crown maintaining strongly it was proof of Jesus’ resurrection and the sceptics maintaining it was nothing. But there are at least 3 separate questions: (1) Is it ancient? (2) Was it from Jesus? (3) Was it produced by resurrection? One could well maintain the answers are Yes, Maybe and No, as well as the more polarised Yes Yes Yes or No No No.

Thanks for commenting.

As you know, I’m rather sceptical of claims that the Shroud of Turin is genuine. I have a few points for consideration:

1. The Image of Edessa is a separate relic connected to the legend of the conversion of Abgar the Black. The relic is based on the head cloth (the Soudarion) in John 20: 7, which mentions it as a separate piece of cloth. This itself is a problem for the Shroud being genuine, because why isn’t there any evidence of the Soudarion having been sewn onto the Shroud?

2. Ancient Jews shrouded dead people with linen strips (the gospels generally speak of “linens” in the plural, which meant separate pieces) rather than with shrouds. This means first that the neat rectangular shape of the Shroud would be anomalous if genuine. Second the current image doesn’t correspond at all to how imaging on shrouded linens would work.

3. The problem isn’t that the herringbone weave was rare in Roman-era Palestine, but that it hasn’t been attested there at all. This is a smoking gun, because scholars and scientists would require very reliable dating to this era in order to accept such an anomalous artifact. However, this type of weave was known in the Middle Ages.

Hi IN, thanks for that input. In my reading, I don’t think I came across much about a single shroud vs strips of cloth – I’ll need to check back on that thanks. I was initially rather sceptical about it all, but Bjorn on the Quodlibeta blog put me onto the Søvik papers, which he was a “sceptical reviewer” for, and he said he thought Søvik had done a pretty fair job. So I concluded only slightly more sceptically than Søvik, though my feeling is similar to yours.

The best explanation of the Holy Shroud is that it was created by Gnostics in the 1st or 2nd century using a crucified victim and methods that have been lost to history. I explain this on my website titled “Canonical Complaint Against Cardinal Dolan.”

U R a shroudie in diguise as many o th commenters. It’s obviously so with comments like “Jesus raised Lazarus from th dead” !! Really!? WOW ! But were U there!? No! Yet U seem so sure that U want everyone 2b a believer to. That is religious fascism. If U had said something like “it is one of several repeating themes in th Bible”. OK good enough. We can have something to discuss. But no, U have 2b a literalist. Believe first n ask questions later. That is th mark of all shroudies. To believe n silence opposition. That is what th shroud inspires. Is that of God? Maybe Ur god.

Hi, thanks for reading and commenting.

But I wonder if you read this post to the end? Did you notice I said: “I think neither side has proved their case or shown the other side to be wrong” and then “I must admit I feel a little sceptical, not based on the evidence, but from an innate doubt that God would work in this way”? Does that make me a “shroudie”?

OK

I have a friend who is very interested in the Shroud if Turin.

She sees other, smaller faces and objects in the background around Jesus’ face.

Does anyone have input regarding this?