Most people who read this blog have some beliefs about Jesus, whether positive (belief in him) or disbelief (that he was divine). And most people know some historical facts about him.

But how do the facts and beliefs relate? Do facts lead to beliefs or do beliefs control the facts we understand?

Are there any historical facts about Jesus, or just beliefs? And if there ARE historical facts about Jesus, how do we know them?

What is a historical fact?

Very few things in this world are certain – some say only death and taxes! 🙂 And things in the past are less certain, because memory can mislead us, reports can be biased.

Nevertheless, just as scientists are confident they can reconstruct our evolutionary past, even though there remain uncertainties, so historians can reconstruct some aspects of past events. The history they come up with isn’t certain, but in many cases it is probable.

So a historical “fact” is something that the consensus of competent historians are agreed is most likely to have occurred.

How do they do it?

Historical reconstruction is based on primary sources (documents and artefacts created around the time being studied) and secondary sources (reports written about the event later). Historians will compare reports to see if there is agreement between them, assess how the events reported fit with known culture and history, assess biases and authenticity, and evaluate which sources are most reliable.

From all this information, they will judge what most likely occurred, what aspects of their history are less reliable and what additional information could assist. Of course it is more complex than that, but that is a rough outline.

The end result is (hopefully) a reasonably well supported outline of events with many aspects less certain or open to debate. If the reconstructed history is generally accepted by competent historians, it can be judged a “historical fact”, recognising that this means a “historical probability”.

This isn’t different in principle to what occurs in science, where there can be uncertain evidence and disagreement among scientists. However in science it is likely to be easier to resolve the disagreement with further experimentation, whereas in history resolution will likely require additional primary soures, which may never be found.

Facts and beliefs

We are all familiar with these ideas in everyday life. For example, I may learn the medical fact that too much exposure to the sun can cause skin cancer, especially in Australia. So I form the belief that I will in future limit my time in the sun and wear sun screen. Knowing the same facts, another person may decide not to change their behaviour, in the belief that they won’t get cancer.

Sometimes there will be facts that we are mistaken or ignorant about. It was once commonly believed that the sun revolved around the earth (geocentrism), but this belief was mistaken. Europeans used to be ignorant that the continent of Australia existed, but it was here nevertheless, as the indigenous people were quite aware!

So we can have wrong beliefs about facts, but they remain facts nevertheless. But of course, sometimes there will be legitimate disagreement about some factual truth. For example, for a century or more, the data on heliocentricity (the sun at the centre of the solar system) vs geocentrism was inconclusive and scientists (then known as “natural philosophers”) were divided on the facts. Eventually, as telescopes improved, the evidence showed that heliocentrism was true.

When facts contradict beliefs

We all like to think that our beliefs are correct and supported by the evidence. But this means that if we come across facts that contradict our beliefs, we can be all too easily prone to put the facts aside and hold onto our beliefs. Our brains and our emotions have many ways of doing this.

- We can be selective about which information we accept as genuine (confirmation bias),

- we can rationalise and reject contrary information (motivated reasoning),

- we can think we know more than we actually do (Dunning-Kruger Effect), and

- we can follow what others in our group or “tribe” think with questioning (group think).

I have examined these tendencies in more detail in Why facts don’t always change our minds.

Facts, belief, history and Jesus

Many times I’ve seen misunderstandings about facts and belief lead to fruitless discussion and argument between believers and non-believers.

Secular historians (historians of whatever belief working in secular universities or organisations) study Jesus more or less as they would any other character in history. They use the New Testament as source documents (not just one document – it is after all a compilation of many documents) along with other primary source material. They don’t privilege the New Testament as a holy book or “the word of God”, and theoretically they put aside their own religious or non-religious convictions while doing historical study. (I say theoretically because none of us can be totally unbiased.)

On this basis, they draw conclusions just as they would when studying any other historical person or event. Some conclusions will be more or less unanimous and can thus be regarded as “facts”, some will be much argued over. Just like with other historical study.

Many aspects of christian belief can thus be regarded as “facts” – my next post, What do the leading secular historians say about Jesus? will outline these conclusions. But many other aspects of christian belief cannot be established so readily, for several reasons.

Insufficient historical evidence

If an event is recorded in only one of the gospels, historians may consider it be lacking sufficient corroborating evidence – for example, Matthew’s story of Jesus’ parent’s travel to Egypt, which doesn’t appear in other gospels and is considered to be unusual and unlikely.

An event beyond historial analysis

Jesus is recorded as performing many healing miracles. Historians have no difficulty accepting that Jesus was known in his time as a miracle-worker. But the reality behind that is harder to establish. Some historians conclude that people really were healed, but still disagree whether it was miraculous or “folk healing”. But others say that believing in healing miracles (or not) is not a historical matter and refuse to come to a conclusion one way or the other.

A matter of belief

Christians generally believe Jesus was divine while non-believers don’t. Historians discuss whether Jesus claimed divinity in his lifetime, or whether that was an early christian belief that was placed in the stories after the event. But they generally (with a few exceptions) are reluctant to make pronouncements on the fact of his divinity because it is a matter on which historians of different religious beliefs cannot agree.

Christians and history

I have no problems as a christian in accepting the broad consensus of historical study of Jesus, and from that basis concluding that belief in Jesus’ divinity is justified. I can believe that Jesus really did heal, and that is the best explanation of why he was known as a healer. And I can recognise that this is my belief, not an established historical fact, though it isn’t contrary to the facts either.

Christians don’t have to be afraid of historical analysis, in fact we can learn from it. In presenting my faith to others, the historical consensus is a good place to begin. Then I can attempt to show why I think the divinity of Jesus is the best conclusion to make. If my faith cannot cope with the historical consensus, then it isn’t a robust belief.

Atheists and history

Atheists don’t have to be afraid of the historical consensus either. If the historians conclude certain things about Jesus (e.g. that he existed and was known as a healer), an honest unbeliever can accept those “facts” and then attempt to show why not believing in his divinity is the more reasonable conclusion.

Unfortunately, it isn’t always like that. Some non-believers confuse history with belief and reject both history and belief about Jesus. But if their non-belief cannot cope with the historical consensus, then it isn’t a robust disbelief.

Jesus + history on this blog

Whenever I address the question of Jesus and history, I always try to separate what is historically true from what is my belief based on the “facts”.

In the next couple of posts I’ll look at the historical evidence for Jesus’ life and teachings, and for the resurrection.

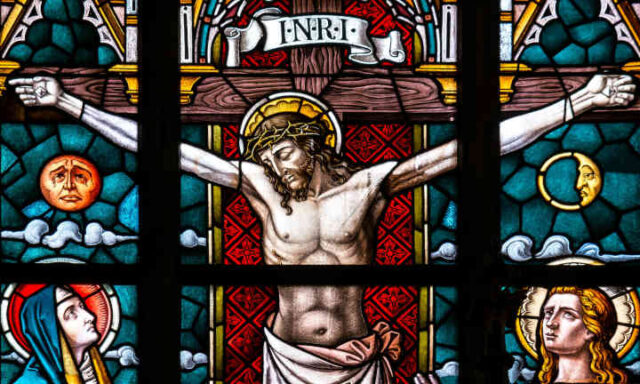

Photo by Pixabay.