I really appreciate philosophy …. most of the time.

Some people think it doesn’t relate to the real world, whether their “real world” is Christian faith or scientific atheism or something else.

But I think philosophy can help us think clearly, clarify viewpoints and expose fallacies.

What makes philosophy useful?

Philosophy examines the big question of life – truth, reason, ethics, God, existence, knowledge, and more. Things most of us have opinions about and want to know about.

We can think about and discuss these matters without being philosophical, of course, but philosophy helps. It can be described as the study of reasons for opinions. Trying to find objective reasons for holding ideas (i.e. reasons why anyone should be able to come to the same conclusion).

So philosophy tries to use clearly stated assumptions and fallacy-free logic to draw conclusions that stand up to scrutiny and have a good possibility of being “right”.

That’s the idea, anyway.

Not everyone agrees, because some think scientific evidence or divine revelation or personal intuition, or even tribal thinking, are the best or only ways to justify what we believe. I think all those processes may have some value, but all can benefit from rigorous thinking and examination.

Others think that philosophy doesn’t relate to the real world, but is simply arguing about words or useless ideas. I think that can be true, but overall I find the rigour of philosophy is often helpful. Sometimes scientists scornful of philosophy could benefit from this rigour.

All this in one book!

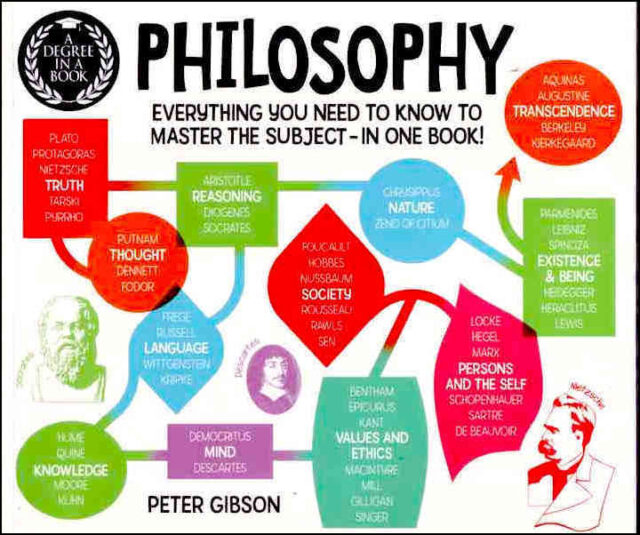

Recently I found this book on a sale table at a bookshop I’d never visited before. Philosophy: Everything You Need to Know to Master the Subject … In One Book! by Peter Gibson.

It looked like fun and comprehensive. And it was!

Everything = everything

The book tries to cover every important philosophical topic, from truth, reasoning and knowledge through existence, mind, persons, thought and language to values, ethics, society, nature and transcendence.

Included amongst all this are brief bios of eminent philosphers down through the ages and their main ideas.

Lots of colour (photos, diagrams, tables and quotes) make it easier and more fun to read.

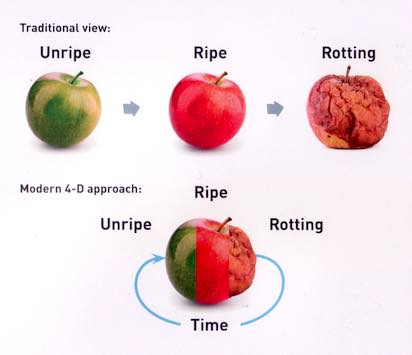

The diagram at the right (not the caption) is from the chapter on existence, which discusses what characteristics define an object, and whether an object is different if some characteristics change, as in the apple.

This question is important when discussing whether each person is the same being from birth to death, or whether our sense of self is illusory (see e.g. Susan Blackmore: there’s no ‘me’!).

Of course neither the author nor me are pretending this book is anything more than the briefest introduction. But its strength is that it outlines issues that can then be followed up via the “suggested reading” at the back of the book, or via search engine or AI.

Interesting philosophical issues

How do we know things?

Knowledge is a tricky thing. We can feel sure we know something and be wrong. We can feel uncertain about something and still be right. So how can we really know something?

Empiricists believe that all knowledge comes from what we can observe or experience. This is the basis of science. But scientific knowledge isn’t always certain. We may observe lightning coming from stormy skies, and if we observe this enough times, we may infer that it always comes from stormy skies, but this type of conclusion is always probable, not certain.

Some of our experiences are known only to ourselves (e.g. our memories, which may be unreliable), and we cannot observe all science, all history, all geography and must rely on others for most of what we know. So one aspect of knowing is comparing experiences and memories, and making judgments about who is a reliable source of information.

But observations and experiences may not be understood correctly, so we may require other criteria for knowing something. Perhaps what we know may need to be consistent with other things we know so that our knowledge is coherent.

Minds

We can observe most parts of our bodies, but our minds are more mysterious. Is the mind a thing or a process, or what? Is it just an aspect of our brain (physicalism), or something quite separate (dualism)? And what does it mean to be conscious, to be “me” rather than “you”? What does it mean to be a “self”?

It seems most natural to think that we are composite beings where our “self” inhabits our body, which is dualism. But evolutionary biology seems to point to us being only physical. And if the mind is separate from the brain, how are they related, how do they influence each other?

So physicalism is the most common view among neuroscientists and philosophers. But this tends to lead to determinism, based on the fact that our brain processes are fully described by physical laws, leaving no opportunity for choice, which makes it hard to hold people morally responsible for their actions.

Consciousness is a big mystery. It seems to be more than just the ability to mentally process information. We can wonder what it’s like to be someone else, but does it make any sense to wonder what it’s like to be a computer?

But it seems that humans could evolve successfully via natural selection without needing to be conscious, so consciousness is the unexplained “hard problem”.

Ethics: how do we decide about right & wrong?

What things are right and what things are wrong? There are several views:

- Deontology: there are universally recognised rules about duties and behaviours which we should all follow.

- Virtue ethics: there are universally recognised human virtues (e.g. bravery, self control) and a good eprson has those virues and behaves accordingly.

- Utilitarianism: we should behave in ways that most improve human wellbeing.

Each view has its difficulties. The first two face the challenge that (i) different people recognise different virtues, and (ii) rules may not be sensible in every situation. Utilitarinism struggles because (i) we can never really know all the effects of many actions, and (ii) the maximum benefit for many may require terrible harm to the few, which doesn’t seem ethical.

But perhaps the biggest issue is: why should we behave ethically anyway? If we can gain for ourselves, why not behave seflishly?

Holding to a religious or political belief may provide a motivation to be more altruistic. Otherwise, we are left with the view that life goes better if we cooperate – which will work most of the time, but there always seem to be people who seek there own advantage above the common good.

Ethical views are worked out in practice via law and justice. Societies have to decide what is “right” or acceptable on a wide range of issues affecting people’s freedom and safety. Most societies believe in some form of human rights, but such rights may not be granted to all. The ethical, religious and political views we hold will often determine answers to these questions.

Transcendence

Some things appear to transcend nature: for example, consciousness, mathematics and logic, natural laws and moral ideals. These things are , perhaps, more easily explained if “nature” isn’t all there is.

But as science has helped us understand nature better, it has become easier to think there may be nothing beyond nature – no God or gods, no supernatural.

There are several philosophical arguments that suggest a God is “behind” nature. Each has its counter arguments.

A second question arises if one accepts these arguments: what is this God’s character. Is he or she personal, caring, interested in order & beauty, etc? Or is God distant and uninvolved with people?

And there are yet further questions:

- How can there be any true morality without God?

- Can humans have free will if God is all-powerful and knows the future?

- If God is “good”, why is there so much evil and suffering in the world?

Just a sampler

This book is just a sampler, a quick outline of many important issues and viewpoints. It provides a good introduction, from which we can further investigate issues we are especially interested in.

This website has pages on many of the issues I have mentioned here – you may want to check some of them out.