Archaeology is a key aspect of historical assessment. It can provide tangible information to confirm or disprove historical texts.

So how does archaeology confirm or disprove the accounts in the Old Testament? Many sceptics say it throws considerable doubt on the accounts as history, while conservative Christians often argue that archaeology proves the Bible.

Who is right? Here is a non-conservative Christian’s assessment of the evidence.

Contents

Artefacts vs text

Archaeology gives us hard facts – foundations of cities, inscriptions, carbon dates, artefacts like pottery or sacred objects, and so on. These evidences cannot lie, but they need to be understood, interpreted and placed in a context. And the remains available for archaeologists to examine represent only a tiny fraction of the material that existed back in the day. The interpretation of ancient documents may be more obvious, but they will have their own biases and perspectives that have to be understood and allowed for.

So archaeology and documents are most useful when they can be used together.

Different times and circumstances

The narratives in the Old Testament, if we put aside the first 11 chapters of Genesis and begin with Abraham, are set in many different Middle Eastern locations and cultural situations over two millennia.

We wouldn’t expect the same amount of archaeological evidence (or documentary evidence) of nomadic herdspeople who didn’t build permanent homes or have government officals keeping records, as we might expect of people settled in cities with buildings made of stone and with kings and priests making records in stone or on clay tablets.

So in considering the light that archaeology throws on the Bible, we cannot expect to find the same level of archeological remains in all periods. So I will consider three separate periods covered by the Old Testament:

- The patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac and Jacob) up until the time of Joseph;

- The time of the exodus from Egypt and settlement in Canaan (the time of Moses, Joshua and the “judges”); and

- The time of the monarchy up until the end of the Old Testament (including king David, the prophet Isaiah and Nehemiah).

Who should we trust?

It should be noted right from the start that there is a wide range of opinion on the historical reliability of the Old Testament narratives. This creates a problem – who do we believe when both sides can seem so plausible? Here is how I have approached it.

Maximalists

Maximalists (sometimes called “Biblical archaeologists”) tend to be conservative Christians or Jews who accept the Biblical accounts as historical unless proven otherwise. They tend to argue that archaeology proves the Bible to be true. But I am left with the suspicion that proving the Biblical accounts to be true so colours their judgment that, in the end, it is the Bible proving which archaeological interpretation is preferred. Nevertheless, I have considered maximalist views on all aspects of this topic – see Ref 4 for some examples.

Minimalists

Minimalists tend to be critical secular scholars who are highly suspicious of the Biblical texts and don’t regard the Bible as historical unless archaeology and other historical documents show otherwise. I tend to feel they can sometimes be over-sceptical, moreso about the Bible than other ancient texts. Nevertheless, I have considered minimalist views on all aspects of this topic – see Ref 5 for some minimalist references.

A thoughtful middle view

If the experts can’t agree, how am I going to judge what is historical? I have tried to examine the arguments on both sides and see which seems best based on clear archeological evidence for the important aspects such as dating, the nature of artefacts and how a city ceased being inhabited.

So I have generally followed the views of critical but not over-critical scholars on the archaeology, while being more open to the texts than they might be. My main guide has been William Dever, an archaeologist with extensive experience in Canaan and detailed presentations of the tangible Canaanite evidence in Ref 1 and a broad outline of Old Testament archaeology in Ref 2, plus recent archaeological reports since those books were written.

1. The patriarchs

The stories of the patriarchs are set in the Early to Middle Bronze Age (around the time 2100 BCE to 1600 BCE). The main characters were nomadic herdsmen, somewhat like today’s Bedouins, living in the fertile crescent. The events described weren’t generally important politically or nationally, and so wouldn’t be likely to be recorded by other sources.

So we wouldn’t expect to have archaeological traces of these people or of the events described, and so far none have been found. So there is no information to verify or disprove the Bible accounts.

But archaeology does provide some useful background information that can be used to assess the Biblical narrative (Ref 2).

- The stories of the patriarchs fit into the nomadic, kin-based, multigenerational, polygamous culture known to be common at that distant time.

- Semitic people did migrate to Egypt, and some did become kings and national officials, as in the Biblical stories of Joseph.

- Some names recorded in cuneiform archives in Mari on the Euphrates River resemble the pattern of names in the Biblical stories.

- Likewise some practices found in texts from Nuzi on the Tigris River (e.g. marriage and adoption customs) are similar to some found in Genesis.

It seems certain that these stories were passed down, adapted and embellished, for more than a millennia before being written down. The fact that they reflect many aspects of that ancient world after all that time suggests to many historians that there was some historical truth to the names or the stories, though likely a lot of legendary embellishment.

Of course conservative (maximalist) scholars tend to accept the stories of the patriarchs as generally true while minimalist scholars generally regard them as totally legendary.

So I conclude that archaeology does little to confirmm or disprove the Biblical accounts of the patriarchs, and our belief or otherwise in these stories must be based on our view of the Biblical text.

2. Moses, Joshua and the “judges”

The Biblical accounts of these important characters take place in Egypt, possibly sometime in the period 1600 to 1300 BCE and in Canaan (modern day Israel, Palestine and Jordan) sometime in the period 1400 to 1000 BCE.

Importantly, these were periods and locations where significant records from other nations have been discovered, and the Israelite people lived for the latter period in cities built of stone, so many remains have been unearthed.

So there are better possibilities for the archaeology to confirm or disprove the Biblical accounts.

Egypt and the Exodus

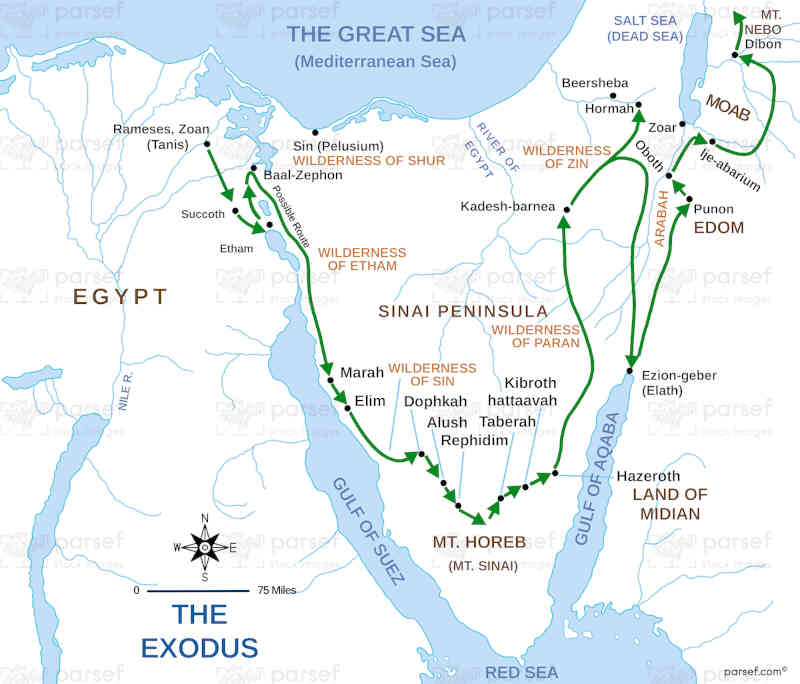

According to the Bible story, the Israelites who had come to Egypt when Joseph was a high official, eventually became slaves making bricks for Egyptian building projects. Then the Israelite Moses, through fortuitous circumstances, became a member of the royal court. Later he became the Israelite leader and after punitive interventions by God, led his people, now numbering something like 2-3 million, out of Egypt and across the Sinai desert to the edge of Canaan.

Archaeological evidence

Like the patriarchs, there is virtually no archaeological evidence for this story. Maximalists accept it as true, though with some exaggeration of numbers, while minimalists tend to say it is totally legendary.

We wouldn’t expect brick-making slaves to leave much evidence behind them, nor would you expect that fleeing slaves would take stone tablets with them and then drop them in the desert for archaeologists to find. And even if they did, what are the chances of such artefacts being found?

But the Israelites are reported to have camped for about 38 years at Kadeah Barnea, just south of Canaan, and archaeologists believe that 2 million people for 38 years would have left some discoverable trace. So this lack of evidence probably counts against the accuracy of the Bible story.

Archaeology in present day Israel has been comprehensive enough to establish the size of cities and hence the likely population of Canaan after the Israelites arrived, and the best estimates seem to be about 60,000 people, and certainly less than 100,000. It is more or less impossible for 2-3 million people to have settled there as suggested by the Biblical text.

(There are other historical and practical reasons to doubt the story in its present form – see Did Moses really lead 2 million people across the Red Sea and into Canaan? – but on this page I am only addressing the archaeology.)

Indirect evidence

However this is some indirect evidence from Egyptian archaeology for some historical basis for the exodus story, though probably with far fewer numbers (Ref 3).

- It is known that Semitic people from the Canaan area did visit Egypt at times in this period, so it wouldn’t be unusual for a group to make the journey from Egypt to Canaan.

- The cities which the Hebrew slaves were said to have helped build were occupied at the required time, and and Egyptian inscription shows an “Asiatic” slave (a term which included Israelites) being whipped while making bricks.

- The names of several people in this story (including Moses) have Egyptian origin, not Semitic.

- Some of the religious practices of the escaping slaves – e.g. the design of the tabernacle (a portable temple) and the ark of the covenant (a sacred object kept in the tabernacle) are very similar to Egyptian designs. These are included among many other striking resemblances between the Exodus text and inscriptions describing Pharoah Ramesses’ victory over the Hittites at the battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE.

- A number of elements in the story use language that reflect Egyptian culture and lore.

I believe we can reasonably say that some fugitives from Egypt ended up in Canaan, perhaps bringing some new religious practices with them. How many and how they fitted in will be discussed later.

Joshua and the conquest of Canaan

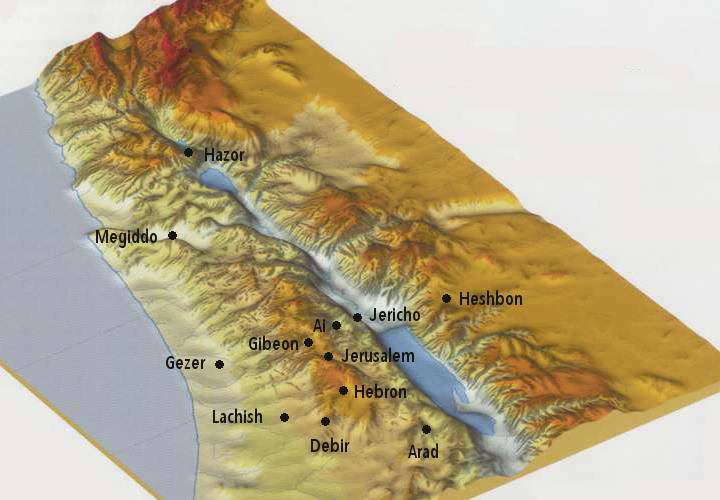

The Bible contains two different stories about the Israelites entering Canaan. In the first half of the book of Joshua, the Israelites under their leader Joshua attack and destroy city after city (including Jericho, Ai, Lachish, Hebron and Hazor), mercilessly killing the inhabitants, until they captured the whole land, 31 cities in all.

However the second half of the book of Joshua and the book of Judges, portray a much slower settlement amongst a growing population of different people groups, with some fighting to be sure, but nothing like that depicted in the earlier parts of Joshua.

Dating

Historians aren’t agreed on the date of Joshua’s entry into Canaan. Maximalists (mostly conservative Christian scholars) favour a date around 1400 BCE, which fits their overall Biblical chronoloogy, while most others believe the best date is around 1200 BCE.

Further complicating this is the disagreements between Amihai Mazar & William Dever vs Israel Finkelstein about Israelite/Biblical chronology. Finkelstein favours dates about 50-100 years later than Dever for the first half of the Iron Age (conventionally about 1200 BCE to 900 BCE). I have generally used dates closer to Mazar/Dever because that seems to be the consensus, but I’ve tried to be flexible. All dates given here are approximate.

The Amarna Letters, letters to the Pharaoh from the Egyptian administrators in outlying areas including Canaan and local chiefs or kings, show that Egypt still occupied and controlled Canaan in 1400 BCE, ruling over many “small, competitive city-states …. desperately vying with each other” (Ref 1).

A major Israelite entry into Canaan would only have been possible after the Egyptians began withdrawing in the late 13th century, so a date around 1200 BCE is most likely.

The late Bronze Age (1300-1200 BCE) was a time of change in the Middle East. Several major societies such as Hittite, Ugarit, and the Old Assyrian and Old Babylonian regimes collapsed, perhaps due in part to drought, resulting in major people movements. Among these movements were Egypt’s withdrawal from Canaan, the invasion of the Mediterranean coast by the sea peoples (predominantly the Philistines) and new settlers moving into central Canaan – refugees from the coast displaced by the Philistines, Arameans and others coming in from the north …. and apparently some refugees from Egypt led by “Joshua”.

Archaeology

There is plenty of archaeological evidence for this period in Canaan.

The Victory Stele of Pharaoh Merenptah (a stele is a vertical stone with inscribed text), dated about 1210 BCE mentions the Israelites as one of the Canaanite peoples supposedly defeated by Egypt. This is the earliest known reference to the Israelites outside the Bible, and confirms their presence in Canaan at that time – although the Egyptian victory claims were propaganda rather than fact.

Several hundred new settlements were established in the twelfth century in central Canaan, which fits with the arrival of the Israelites and others.

Many of the cities mentioned in Joshua have been discovered and excavated. There are certainly signs of destruction and warfare at many of them. Trouble is, not much of this extensive archaeology clearly supports the Biblical account, whichever date we give for it. Here is the archaeological evidence for cities the Bible says were totally destroyed, some by fire (Ref 2):

Heshbon & Dibon (Transjordan)

While Moses was still their leader, the Israelites were reported to have conquered these Amorite cities. But archaeology so far suggests that neither existed as cities at that time.

Jericho

Jericho’s walls did indeed fall down (see Did the walls of Jericho really fall down?) and many details of its destruction match the Biblical account. But the destruction was probably about 1500-1550 BCE which doesn’t fit either of the commonly proposed dates, and Jericho was barely occupied for centuries after. It seems most likely that the Israelites attacked a small settlement around 1200 BCE, but this story was conflated with the earlier, larger destruction, probably by Egyptians.

Ai

The Bible says the Israelites captured and burnt Ai and killed everyone in it. But the archaeological evidence is confused by disagreement about which of two sites should be identified as Ai.

The Hebrew meaning of “Ai’ is “ruin heap”. Most archaeologists identify the site Et-Tell (which also means “ruin” in Arabic) as Biblical Ai. Et-Tell was indeed destroyed, but more than a millennium before, and remained a ruin until a small village was established sometime after the Israelites arrived.

But maximalists argue that`Et-Tell doesn’t fit the Biblical description and have identified a nearby site, Khirbet el-Maqatir, as the correct location for Biblical Ai. It was destroyed about 1400 BCE and there is evidence of burning, which fit their early chronology. But the current consensus of archaeologists is that Khirbet el-Maqatir is too small (it appears to have been “a small fortress” rather than a city of 12,000 people as reported in Joshua 7 – although, confusingly chapter 6 says there were few fighting men there), and the artefacts found there don’t fit either the early or late chronology.

I’m prepared to go with the consensus on this, and say that the archaeology doesn’t confirm the Biblical account, but it may still turn out that Khirbet el-Maqatir is found to be the correct site for Ai.

Megiddo, Lachish

Megiddo and Lachish were important cities located in different parts of Canaan. Apparently both were conquered several times, once about 1200 BCE, then rebuilt as Canaanite cities and destroyed again about 1150 BCE. These dates are much too late for the early chronology but may be consistent with the later chronology. The archaeology doesn’t support the total annihilation of Canaanites as depicted in Joshua 1-12, but may be consistent with the slower assimilation portrayed in Joshua 13-24 and Judges.

Hazor

Hazor was one of the largest cities in Canaan and was said to have been captured and burnt by Joshua, religious objects destroyed and all its inhabitants killed. The city was indeed destroyed violently around 1250-1200 BCE, plausibly by the Israelites. But no weapons were found, suggesting it may have destroyed in a civil uprising against the ruling class.

However some archeologists argue for an earlier destruction by Joshua around 1400 BCE, and then a rebuild and final destruction but a later generation of Israelites in the 12th century, which is also hinted at in the Bible. Either way, Hazor can be seen as some support for the Biblical account.

Bethel

The soldiers from Bethel were reported to have been defeated by Joshua, but the Bible doesn’t give a clear indication of the city’s fate. The archaeology shows that Bethel was destroyed around 1200 BCE, but perhaps by Philistines rather than Israelites.

Remaining cities

Joshua 12 records 31 Canaanite cities said to have been destroyed along with their kings and people. Of the 25 cities not discussed above, only one (Jokneam) appears to have been destroyed as described in Joshua 12, 10 weren’t destroyed as described, and 14 are unclear (mostly because the sites have not been identified) (Ref 1).

Conclusion from the archaeology

Of the 33 sites surveyed, none appear to have been destroyed by Israelites around 1400 BCE and only 3 in 1200 BCE – and it is uncertain who was responsible. 14 sites don’t appear to support the Joshua 12 account. Half the sites cannot be identified.

If we reject the rapid conquest account in Joshua 12, the gradual settlement of a much smaller group of Israelites, as described in Joshua 13-24 and Judges, looks much more like what has been found in the archaeology.

Before the monarchy

The Bible describes the period between the supposed conquest about 1200 BCE and the establishment of the monarchy (about 1000 BCE) as a time of constant fighting between the Israelites and Canaanites remaining in the land and the adjacent nations such as the Philistines, Midianites and Amalekites.

The archaeology shows a diverse multicultural region, with many groups jostling for their position. It is estimated that in the “hill country” that later became Israel and Judah, the population grew from perhaps 12,000 to perhaps 60,000. This increase must have included many newcomers into the region, often (it is believed) fleeing from larger controlling city states. It is reasonable to conclude this included a relatively small group from Egypt under “Joshua”.

Initially this increasing population tended to live in small settlements, and only later coalesced into the kingdoms of Israel and Judah as described in the Bible.

Thus, while there is little direct archaeological evidence for the Biblical account, the book of Judges rings true to what is revealed by archaeology, with one exception. The archaeology, consisting of shrines, altars, religious figurines and even some inscriptions, reveals a generally polytheistic society with little evidence of monotheism. For most people at this stage, Yahweh was a tribal god with a consort. It appears that Jewish monotheism grew out of this, possibly because of the influence of the Israelites from Egypt.

My conclusion, based on Ref 3, is that the fugitives from Egypt became the Kohanim (Jewish priests supposedly descended from Aaron, Moses’ brother). DNA studies indicate that while the majority of Jews are genetically similar to descendants of other Canaanites, the Kohanim are genetically a little different.

3. The monarchy

It is from here on that archaeology most supports the Biblical accounts.

The Bible records that about 1000 BCE, Israel & Judah became a united monarchy under Saul, David and Solomon. But the united monarchy soon broke apart with separate kings in the north (Israel) and Judah (south). Israel was invaded and its people deported by the Assyrians in about 732-722 BCE and the region depopulated. Famously, while Assyria invaded Judah it was unable to capture the capital Jerusalem, an event seen by the prophet Isaiah as providential. So Judah remained, for a time.

The Assyrians were replaced by the Babylonians as the major regional power, and they conquered Judah in 597 BCE. Over the next decade most of Judah’s elites were taken into captivity in Babylon. They remained there for about 60 years, but after the Persians defeated the Babylonians the exiles were allowed to return.

Archaeology & history

Most of these events are confirmed by archaeology and the history of surrounding nations. This is where most claims of archaeological support for the Bible are made. There are too many examples to list here, but here are some of the main ones.

Sennacherib vs Hezekiah

Perhaps the most famous archaeological confirmation of an Old Testament account is that of the Assyrian invasion of Israel and Judea, recorded in no less than three books, Isaiah, 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles. The Assyrian army of Sennacherib had conquered every city it came up against, until Jerusalem. King Hezekiah had prepared for a long siege. He had the city walls strengthened and had a tunnel built to channel spring water from outside the city inside. The army laid siege but eventually withdrew. The Bible says that God destroyed the Assyrian army. Sennacherib returned to Assyria and was later murdered by two of his sons.

Most of this epic confrontation is conformed by archaeology:

- The remains of the strengthened wall and the water tunnel have been found. Some say the tunnel was built by a later king, but it definitely fits the circumstances Hezekiah found himself in.

- The Lachish reliefs, wall carvings from King Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh, show the Assyrian siege of the Hebrew city of Lachish, which was part of the same campaign as the Jerusalem siege.

- A clay “cylinder” found in Sennacherib’s palace confirms that the Assyrians laid siege to Jerusalem but, unlike all the other cities of Israel and Judah, they were unable to capture it. Of course Sennacherib puts a positive spin on it but it was a failure on his part. Historians believe the Assyrian army was much smaller than that claimed by the Biblical authors, but that something unusual happened to send the army away.

Events confirmed by other nations

Sennacherib vs Hezekiah isn’t the only place where records from other nations confirm the Biblical accounts, though with a different emphasis.

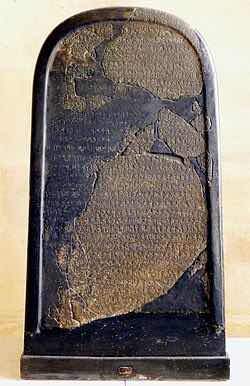

The Mesha stele

The Mesha Stele or “Moabite Stone”, dated about 840 BCE, tells the story of a war between Israel and the neighbouring country of Moab. The Bible (2 Kings 3) recounts the story from Israel’s perpective, while the stele tells the story from King Mesha of Moab’s perpective. The two accounts agree in many ways and so confirm each other. The stele also confirms the name of Omri, the Israelite king.

The Ketef Hinnom scrolls

The Ketef Hinnom scrolls, dated about 600 BCE, are two small silver scrolls found in a burial. They contain the text of the priestly blessing in Numbers 6:24-26 and are the earliest known piece of text found in the Hebrew scriptures. This means either that the book of Numbers was in existence at that time or, more likely, that the blessing found in Numbers was in use at that time and later included in Numbers. Some scholars had previously thought the blessing came into use later.

The Babylonian Chronicles

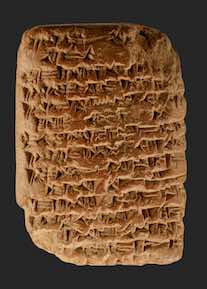

The Nebuchadnezzar chronicle, dated about 595 BCE, is one of 45 tablets recording major events in Babylonian history. It tells of the Babylonian capture of Jerusalem and the replacement of king Jeconiah with the subservient king Zedekiah.

The Lachish ostraca

The Lachish ostraca, dated about 590 BCE, are a series of letters written in ink on broken pottery, discovered in the excavation of the ancient city of Lachish. They are letters written to a military commander in Lachish by an officer in an outlying town. Among other things, the letters appear to refer to concerns about the invasion of Nebuchadnezzar, which occurred not long after. The name of God, YHWH is commonly mentioned in the letters. I’m not sure if these letters corroborate the Bible much, but they certainly provide background.

The Cyrus cylinder

The Cyrus cylinder, dated about 538 BCE, is a clay cylinder about 22 cm long, with text written after the Persian Cyrus conquered babylon in 539 BCE. While it doesn’t mention the Jewish people, it sets out Cyrus’ enlightened way of dealing with other nations and other religions, which supports the Biblical statements in Ezra about Cyrus repatriating the Jewish people and allowing them to re-build their temple.

Mentions of Biblical names

The Tel Dan stele

The Tel Dan stele, dated to the 9th century BCE, is a broken piece of stone with an inscription that mentions four Biblical characters – the kings David (the earliest archaeological reference to him), Jeroram, Ahab and Ahaziah. The phrase “house of David” confirms David’s status as the head of a line of kings of Judah.

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, dated about 825 BCE, is a 2m tall 4-sided stone obelisk found in the city of Nimrud in Northern Iraq. It contains in relief 4 scenes of each of 5 kings bringing tribute to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III. One of the kings is Jehu of Israel (or less likely, Jehoram) who is said to be from the house of Omri. This doesn’t agree with the Bible, but it confirms Omri’s status as the head of a small dynasty.

Other mentions of Biblical names:

- Bullas (soft pieces of clay with the impression of a seal) from king Hezekiah, Gedaliah, son of Pashhur, and Baruch ben Neriah.

- Other steles: king Jehoash of Israel, king Menahem of Israel.

- Other inscriptions: king Ahaz of Judah, king Manasseh of Judah, king Ahab of Israel, king Hoshea of Israel.

Summary of archaeology post 1000 BCE

It is clear that many inscriptions mention kings and events in Israel and Judah in this period generally confirm the Biblical accounts of battles, winners and losers, tribute paid, etc.

It is therefore easy to conclude that in this period archaeology does confirm the Biblical account, as much as archaeology is able to do that. It is of course unable to confirm more personal details and the intervention of God in the affairs of these nations, but it does show that those who wrote and edited the texts of the Jewish scriptures had good records of events from about 1000 BCE onwards.

The Bible and archaeology

Does archaeology support the Old Testament historical accounts?

The answer is: “Yes and no.”

It seems clear that the three different periods we started with have different relastionships between archaeology and the Old Testament

- The patriarchs up until the time of Joseph: little archaeology remains from nomadic peoples, so archaeology neither confirms nor disproves the Old Testament accounts.

- The exodus from Egypt and settlement in Canaan: there is a reasonable amount of archaeological information, and it tends to show that many of the Biblical accounts are exaggerated or legendary, though with some factual basis.

- The time of the monarchy: there is plenty of archaeological information which generally confirms the historical accounts in the Bible.

Archaeological apologetics

If you search on the internet for words like archaeology, Bible, prove, etc, you’ll find literally dozens of sites looking at this question. Almost certainly, most of them will be Christian apologetic sites. (I’ve referenced a few below, but there are many more.)

As a Christian myself, it pains me to have to report that many of their conclusions are not really very fair to the evidence.

As I’ve tried to show on this page, there is plenty of evidence for the historical events of the first millennium BCE. And these sites generally report this evidence accurately.

But as I’ve also tried to show, there are places where the evidence makes the Biblical accounts doubtful at best, and sometimes quite exaggerated or even fanciful. But this evidence is rarely mentioned on these sites.

I think the problem is that these are very genuine Bible-believing Christians, and their aim isn’t really to find the truth and show it, but to find ways to show that what they already believe about the Bible is true. And to ignore or explain away those things that don’t seem to fit.

And so they make very generalised statements that “archaeology proves the Bible” when that is only partly true. And so give trusting Christians confience in conclusions that they may later realise are not entirely true. And sometimes this leads them to give up their faith, because they feel they were wrongly informed.

There is, I believe, a better way.

I believe we can trust the clear outcomes of archaeology, while remaining open to it being mistaken in places, and then accept that this is the Bible God has given us. Archaeology becomes an exciting adventure in discovering what the Bible actually is.

The last word

“If you take the Bible as a whole, you see a process in which something which, in its earliest levels (those aren’t necessarily the ones that come first in the Book as now arranged) was hardly moral at all, and was in some ways not unlike the Pagan religions, is gradually purged and enlightened till it becomes the religion of the great prophets and Our Lord Himself. That whole process is the greatest revelation of God’s true nature. At first hardly anything comes through but mere power. Then (v. important) the truth that He is One and there is no other God. Then justice, then mercy, love, wisdom.”

“By the end of the twentieth century, archaeology had shown that there were simply too many material correspondences between the finds in Israel and in the entire Near East and the world described in the Bible to suggest that the Bible was late and fanciful priestly literature, written with no historical basis at all. But at the same time there were too many contradictions between archaeological finds and the biblical narratives to suggest that the Bible provided a precise description of what actually occurred.”

The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the origin of its sacred texts By Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman

References

- Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. William Dever, SBL Press, 2017. A detailed description of the archaeology of the period 1200 BCE to 600 BCE.

- Has Archaeology Buried the Bible? William Dever, Wm B Eerdmans, 2020. A summary of Old Testament history from Abraham to the Babylonian exile.

- The Exodus. Richard Elliott Friedman, HarperOne, 2018. A review of the evidence for a small migration of “israelites” from Egypt to Canaan.

- Bible apologist (maximalist) references:

- Archaeology: Biblical Ally or Adversary? Paul Maier, Christian Research Institute. An old artricle by a historian, now updated.

- Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology. Contains many articles about the archaeology of Biblical cities.

- Major Archaeological Discoveries That Confirm the Bible’s Historicity. Cauldron Pool. An extreme right wing political site that includes support for a conservative reading of the Bible.

- How Has Archaeology Corroborated the Bible? Christian Publishing House.

- How does archeology confirm the Bible? Bible Ask.

- How does archaeology support the Bible? Got Questions.

- 10 Crucial Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible. John Currid, Crossway.

- Minimalist references

- Ze’ev Herzog and the historicity of the Bible. (Noah Kennedy, 2015)

- Unveiling Megiddo / Armageddon – The Mother of All Tells | Full Story with Prof. Israel Finkelstein. YouTube.

- The Bible unearthed : archaeology’s new vision of ancient Israel and the origin of its sacred texts. Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman

- Exodus: How Archaeology Challenges the Biblical Account. Marko Marina

- Did the Israelites really conquer Canaan? Binyamin Zev Wolf.

- Middle assessments

- List of inscriptions in biblical archaeology. Wikipedia.

- Was there an exodus? Joshua Berman, Mosaic.

- The Iron Age, Amihal Mazar. In The Archaeology of Ancient Israel. Amnon Ben-Tor (editor).

- History and Theology in Joshua and Judges. Dennis Bratcher.

- Biblical Historical Context A well researched site by an enthusastic amateur.

- What if the Bible’s Violent Conquest of Canaan never actually happened? Adam Erickson. A christian pastor explain why it is good to doubt the historicity of Joshua’s conquest of Canaan.

Main photo: archaeological excavations of chambered gate at Hazor (Wikimedia Commons).

Fertile Crescent map from Wikipedia.

Exodus map – Free Bible Maps.

Photo of Amarna letter was donated to Wikimedia Commons by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Photo of Mesha stele from Wikipedia.

Photo of Tel Dan stele: Wikipedia.

You may also like these

Feedback on this page

Comment on this topic or leave a note on the Guest book to let me know you’ve visited.