This page in brief

This page sets out what the gospels tell us about Jesus and how he would have been understood in the culture of his time. It is based on the conclusions of Bible scholars and historians, and there is an extensive reference list of New Testament passages and scholars’ writings at the end.

Essentially, historians conclude that Jesus is best understood as one of a long line of Jewish prophets, who warned of God’s judgment on Israel if the people didn’t establish a society based on justice and faith. Those who don’t call themselves christians will not think God was really speaking through him, because they probably don’t believe in God. Those who are christians will think God was speaking and acting through him, because he was the “son of God”.

Basis of this page

The question of Jesus and history (i.e. whether the gospels give an accurate account of Jesus’ life) is discussed elsewhere. Here I have mostly allowed Jesus’ words and actions to speak for themselves. But I also consider, more briefly, the remainder of the New Testament, because its writers lived close to the events of Jesus’ life and were in a far better position than we are to interpret what was going on. I have based this material on a number of references listed at the end, but I have been most influenced by AM Hunter, Michael Grant, Richard Bauckham, NT Wright, Maurice Casey and John Dickson.

These pages include many references to the New Testament, mostly in footnotes (which are shown at the bottom of this page). If you are not familiar with the New Testament, or don’t understand how to look up the references, you can read A quick introduction to the Bible.

Jesus’ life in outline

Jesus, or Yeshua ben Yosef (son of Joseph), was born about 5-7 BCE and grew up in a small village in Galilee in Israel, at a time when Israel was occupied as part of the Roman empire. His father was a carpenter, and he likely learnt his father’s trade. The family (he had several brothers and sisters) would not have been as poor as many, but they probably weren’t all that well off either.

Sometime after he turned 30, in about 28 CE, Jesus began to move around Galilee, teaching and healing. In the manner of a rabbi of his day, he gathered a group of disciples around him, whom he instructed in greater depth, and sent out on teaching and healing missions. Occasionally he travelled the several days’ journey to the Jewish capital, Jerusalem, to attend Jewish festivals (religious observances).

In possibly the third year of his public ministry (30 CE, though this isn’t certain), while in Jerusalem for the Passover feast, Jesus confronted the Jewish religious authorities in argument and in a forceful demonstration in the temple (the most holy Jewish location) protesting against religious corruption. This provoked the authorities to arrange to have him executed by the Romans.

But shortly after his execution, his previously demoralised followers claimed he had appeared to them alive, having been raised from death. Whatever the truth of the claim (discussed in Was Jesus raised from the dead?), certainly his tomb was empty. His followers boldly spread the word of Jesus’ life and mission so vigorously that within 3 centuries the movement had taken over the Roman empire.

Thus it was that an obscure carpenter’s son from a backwater on the fringe of the Roman empire became possibly the most influential person who ever lived, and the religion he began is believed by a third of the entire world.

Jesus the ethical teacher

The most common view of Jesus in western culture is that of a great and innovative moral teacher who emphasised that we should all love one another (“love” in the New Testament generally has the meaning of sacrificially putting another person’s interests before your own). While this is certainly true, many of his teachings were not original but echoed those of other teachers of his day. For example:

- Some parts of the “Lord’s prayer” 1 are similar to, though briefer than, portions of the “Eighteen Benedictions”, used in synagogue worship.

- Hillel and Shammai were two influential, and differing, rabbinical teachers a generation before Jesus, and he sometimes referred to questions discussed by them, and some of his sayings appear to be derived from Hillel. 2

- Jesus’ teaching is recognised as being in the form of “midrash” (rabbinical commentary on the Jewish scriptures often used in Jesus’ day).

However Jesus gave many teachings greater depth or new twists, for example:

- He turned the external morality of the Old Testament law and Jewish custom into more stringent matters of the heart and attitude. “Do not kill” became “do not hate”. “Do not commit adultery” became “do not lust”. 3

- Whereas the Old Testament limited revenge to what was just, Jesus said we should go much further and forgive and love our enemies.4

- The Jewish culture saw wealth as a sign of God’s blessing, but Jesus said God’s blessing was specially with the poor and marginalised, and that materialism was a major barrier to knowing God. 5

- He lived out this belief by habitually associating with, and affirming, the poor and marginalised. 6

- Jesus downplayed the numerous rules and religious observances of pious Jews, urging greater attention to justice and mercy. 7

- He summed up his teaching as “loving God whole-heartedly, and loving our fellow humans as ourselves”. 8

Important and life-changing as Jesus’ teachings were, his main emphasis was not on pleasing God by living rightly. Rather, as we shall see, Jesus saw himself as beginning a new community which lived in the light of God’s forgiveness, and these new behaviours were what God is calling from those who had received that forgiveness.

Jesus the “messiah”

The Jewish kings (600-1000 BCE) were seen as “anointed’ by God, and the greatest king of all was David, who reigned almost a millenium before Jesus. For centuries, the Jews had longed for David’s “son” (i.e. descendent), anointed by God, to restore peace, prosperity and freedom to Israel. The Hebrew word for “anointed” was “mashiah” (= Messiah), which in the Greek of the New Testament was “christos” (= Christ). So calling Jesus “the Christ” was to claim that he was God’s chosen saviour of Israel. But Jesus had a different type of saviour in mind.

Jesus was reticent about claiming to be the Messiah, but others gave him this title, especially after his death,9 and scholars generally agree that “Messiah” is the best description of who Jesus was. His reticence was probably because the people of his day were expecting a warrior Messiah who would free them from subjegation to Rome, and he wanted to avoid this disastrous misunderstanding.10 So what sort of Messiah was he?

God is the all-powerful ruler of the world, but he has chosen to allow people freedom to choose how they will act. This has unfortunately resulted in much evil and misery in the world. But Jesus’ great message was: “The time has come when God is invading history, establishing his rule on earth and beginning to put things right.” 11 He invited people, especially the poor and down-trodden, to voluntarily come under the rule of God, expressed through him as Messiah, receive forgiveness, and live a new life in a new community.12 One day, God’s rule (= God’s kingdom) would be made complete, but for now, people face a choice. 13

For the common people, poor, oppressed by the Romans and despised by the religious elite, this was exciting news. For the Jewish nation, seldom free in centuries, it should also have been good news, but because it challenged the status of the elite, many opposed him.14

The “kingdom of God” is thus the central theme of his teaching. Mark’s gospel summarises Jesus’ teaching this way: “The right time has come, and the Kingdom of God is near! Turn away from your sins and believe the Good News.” (Mark 1:15) And Luke records this statement by Jesus: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has chosen me to preach the Good News to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives, and recovery of sight to the blind; to set free the oppressed, and announce the year when the Lord will save his people.” (Luke 4:18-19)

Historian Michael Grant: “Jesus [believed] he himself was inaugurating God’s kingdom upon earth ….. The whole of Jesus’ moral teaching was secondary and subordinate to this conviction. ….. [He placed] exceptional emphasis on the eligibility of sinners for the Kingdom. For since, as soon as they had repented, they would be forgiven ….”

Jesus also predicted his own death, and taught that his death would be redemptive (Michael Grant: “Jesus [believed] that his death was destined to save the human race.”). In this, Jesus saw himself as the fulfilment of the prophecies in the prophet Isaiah of a servant who would suffer and die for others.15

Jesus’ most characteristic method of public teaching was to speak in parables (stories with a punch line), and the main point of many of the parables was the Kingdom of God.16 Time and time again, Jesus portrayed his ministry as the beginning of a dynamic movement to bring healing, release from bondages and justice to the victimised; undoing the works of the devil (sickness, bondage and oppression), and eventually judgment on all that is evil. 17 He urged his hearers to understand what was happening before their eyes, and respond.18 A M Hunter: “all through [his] ministry there rings a note of terrible urgency, as though a crisis uniquely fraught with blessing or with judgment for ‘this generation’ in Israel were upon them”.

So in a sense, Jesus was challenging the might of Rome, but not in a military way. Rather, his claim to be Lord 19 subverted Caesar’s similar claim, and implied that his followers should place allegiance to him above allegiance to the empire.

Miracles

Jesus’ miracles, like his ethical teachings, are to be understood in the context of the Kingdom of God.20 A M Hunter: “the mighty works of Jesus were the reign of God in action, outgoings in power to sick and sinful people of that love which was central to the kingdom of God.” Jesus’ miracles included healings and exorcisms,21 which demonstrated “the oppressed being set free”, and miracles of nature,22 showing God’s rule over his creation. Most miracles were in response to people’s faith, and it was reported that where there was no faith, Jesus did few miracles. 23

But can we believe in miracles in this scientific age? Were they not just the beliefs of superstitious and credulous people, who saw miracles everywhere, or legends that grew up years later? The scholars do not think they can be dismissed this easily, for example:

- While many Jews were believed to have the power to exorcise, only two living in the first century (Honi the Circle-drawer and Hanina ben Dosa) were credited with miracles, and they were not miracle workers in the way Jesus was, but pious Jews who each reportedly had one prayer dramatically answered. So there was not a strong belief in such miracles and no other accounts like those about Jesus.

- Scholars are quite certain that the miracle stories were not later legends, but believed from the beginning. J P Meier: “The miracle traditions about Jesus’ public ministry are already so widely attested in various sources and literary forms by the end of the first Christian generation that total fabrication by the early church is, practically speaking, impossible.”

- So people of Jesus’ day genuinely believed he worked miracles, but could he really have done so? Scholars, speaking as scholars, are not prepared to say. Many say that is not a question that historians can answer, but each of us can choose what we believe. Graham Stanton: “Few doubt that Jesus possessed unusual gifts as a healer, though of course varied explanations are offered.” If you believe there is no God and the universe is a closed system governed only by natural laws, then you will need some other explanation, but if you believe God may exist, you can remain open-minded.

Changing ideas about God

Jesus was a Jew who followed the customs of the religion he learnt as a child – he knew the Jewish scriptures (the Tanakh, which is now also the Old Testament of the Bible), he attended the synagogue and travelled to Jerusalem several times for important festivals. 24 Yet he was an outpsoken critic of the religious establishment and many of his teachings overturned Jewish traditions and even the contemporary understanding of the scriptures.

- To most Jews, and followers of other religions too, God was seen as a distant and demanding deity, but uniquely, Jesus viewed God as his “dad” and encouraged his followers to do the same. 25 A M Hunter says studies show that this “familiar” approach to prayer and a relationship with God is unique in the ancient world, and it offended the religious authorities. 26

- The Jews knew that God loved and cared for them, but their understanding fell short of the loving God Jesus portrayed – a God of extravagent love who welcomes the most outrageous “sinners” if they turn to him. 27

- On several occasions Jesus referred to commands in the Jewish scriptures, then said “but I say to you” and gave a new, and generally more demanding teaching.28 He thus effectively placed his teachings above those they believed to have come from God.

- In the Jewish religion, God punished sin unless people sought forgiveness, which was obtained by animal sacrifice at the temple in Jerusalem. 29 But on many occasions Jesus announced God’s forgiveness to those who had faith in him, without any sacrifices. 30

- Pious Jews of Jesus’ day observed a myriad of rules (most not in their scriptures) to keep themselves spiritually “pure”, and looked down on those who were not so observant as inferior “sinners”. 30 But the Messiah was known as a “friend of sinners” and outcasts, a sign that God’s Kingdom was inclusive, not exclusive.31 And he taught that many of the practices were unnecessary. 32

- The Jewish religion was based on a covenant (= agreement) with God, entered into centuries before at the time of Moses. 33 This covenant required the Jews to obey a bunch of commands given by God. However, during his last meal with his disciples (the “Last Supper”), Jesus inaugurated a new covenant, that would be based on his death and their faith. 34

These are amazing teachings for a monotheistic Jew, and can only be explained by the fact that Jesus was establishing God’s kingdom, and all things were being made new. As he said in Luke 16:16: “The Law of Moses and the writings of the prophets were in effect up to the time of John the Baptist [Jesus’ cousin and predecessor]; since then the Good News about the Kingdom of God is being told, and everyone forces his way in.”

Needless to say, the religious authorities did not take kindly to this challenge to their traditions, and their authority. The gospels contain a number of stories about them challenging Jesus and him condemning their lack of concern for God and God’s oppressed people. 35

What he said about himself

Jesus’ words and actions give strong indications of who he believed himself to be:

- His claimed to forgive sins, to re-interpret the scriptures on his own authority, to institute a “new covenant” and to be the ultimate judge of all (as outlined above), were seen by his opponents and followers alike as de facto claims to divine authority and status. A M Hunter: “[Jesus] knows himself uniquely authorised by God. He acts for God; his doings are God’s doings.”

- Many times Jesus made claims of the form “I am ….”. These are interesting for two reasons. Firstly, God revealed himself in the Tanakh using the words “I am who I am”, and all Jews recognised that Jesus was thus equating himself with God. Secondly, Jesus went on to say he was “the resurrection and the life”, “the light of the world”, “the way, the truth and the life”, and more – amazing claims. 36

- As we have seen, he saw himself as both the Messiah, who was seen as God’s special representative on earth, and the “suffering servant”. He also called himself “the Son” and called God his father in a way that no-one else could 37 – A M Hunter: “Jesus claims that he alone truly knows God as Father”. Finally, he most often called himself the “Son of Man” an ambigous title but one which the book of Daniel in the Tanakh suggests also indicates his divinity. 38

Thus, while some scholars argue that Jesus would have been appalled to be worshiped as divine, most consider that the belief of the New Testament writers that Jesus was in every sense the “Son of God” was based on his own words and actions. N T Wright: “Jesus was claiming, at least implicitly, to be the place where and the means by which Israel’s God was at last personally present to and with his people.” P J Thomson: “the fact that, after his death and resurrection his disciples proclaimed him as the Messiah can be understood as a direct development from his own teachings.”

Understanding Jesus today

What can we believe about Jesus today?

It seems to me there are three possible positions one could take:

1. We may believe the stories about Jesus are unreliable, and we cannot be sure of much more than that he existed, had a public teaching and healing ministry and was executed. Any further belief we have in Jesus comes not from the historical evidence, but from faith. This is broadly the view of some of the more critical and sceptical scholars (e.g. the Jesus Seminar, Borg and Crossan), but is contrary to the views of the majority of historical scholars, and consistency requires one to consequently disbelieve much of ancient history.

2. With the majority of historians, we may accept the historicity of much of the gospels, but be unwilling to believe in the supernatural aspects of the story, and thus disbelieve in the claim that Jesus was the “Son of God”. This was the view of the late Maurice Casey and Michael Grant.

3. If, with the scholars, we broadly accept the historicity of the gospels, and are willing and able to believe Jesus was a truthful person, we will join christians from Jesus’ time until now in accepting his claims to be divine and that he began the kingdom of God on earth. This is the view of scholars such as N T Wright, A M Hunter, Richard Bauckham and John Dickson. It is not capable of being proven, but it is considered by many to be the most reasonable alternative.

A M Hunter quotes John Duncan: “Christ either deceived mankind by conscious fraud, or he himself was deluded, or he was divine.” View#1 avoids this trilemma by throwing the historicity of Jesus’ words into doubt, but effectively requires that the early church was either deceiving or deluded. View #2 implies Jesus was mistaken. View #3 accepts that he was divine.

Disbelievers point to problems: possible historical errors, apparent anomalies in Jesus’ teaching, and the alleged impossibility of the miraculous. But while scholars recognise many of these problems, the consensus of historians generally supports belief, and certainly does not prevent a thoughtful twenty-first century person from believing. For example, Bible scholar Bart Ehrman, formerly a christian but now a non-believer, says he doesn’t think the difficulties with the Bible should lead to disbelief – it was the problem of evil which led to his ceasing to be a christian.

What is the relevance of Jesus’ teaching today?

If Jesus’ main message was the dawning of the kingdom of God on earth, and a major change in the relationship between God and the Jews, are his teachings relevant two millennia later and outside that context?

It seems to me that, if Jesus was mistaken, then his ethical teachings can be added to the teachings of other sages, but he is not in any way “special”. But if you believe Jesus was Lord, and inaugurated God’s kingdom on earth back then, he is still Lord today and he is still calling people into that kingdom today. Believers still live under God’s rule today, most of his teachings are still relevant, although some of the applications will not be:

- God’s kingdom is now well established, not just beginning, so some of Jesus’ warnings which related specifically to the Jews or the commencement of the kingdom will no longer be relevant, but the general thrust of the warnings will still be relevant.

- We can still recognise the truth of Jesus’ teachings on ethics being a matter of the heart more than just outward observance. And we can still apply his teachings of love, non-violence and serving others, though some of the ethical issues will be different.

- Some people still need to see God as a loving father rather than a stern or angry killjoy.

- Jesus still calls all of us to recognise God’s kingdom among us, and to voluntarily accept God’s rule and turn away from our own ways. We still need to recognise our need of forgiveness for going our own way.

- Jesus still calls his followers to live lives of sacrificial love in service of others, and to subvert the competitive and selfish world system by love, though the issues we will deal with may be different.

Books and papers used in preparing this page

I have included brief notes on the references I found most helpful.

- Richard Bauckham: Jesus: a very short introduction. An excellent book that packs a lot of good information into a very few pages.

- M Bockmuehl, Cambridge University: The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. A useful reference because it contains essays by a number of scholars on a variety of important topics.

- M Borg: Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time.

- M Borg & J D Crossan: Last Week.

- M Borg & T Wright: The meaning of Jesus: Two visions.

- Maurice Casey: Jesus of Nazareth. A non-believer and an expert in the Aramaic language that Jesus would have spoken, who accepts the gospels as a good basis for history, and treats Jesus with respect. I learnt a lot from this book.

- Steve Chalke & Alan Mann: The Lost Message of Jesus.

- Dr J Charlesworth, Princeton Theological Seminary (ed): Jesus and Archaeology

- Dr J Charlesworth, Princeton Theological Seminary & Petr Pokorny, Univerzita Karlova (eds): Jesus Research: an international perspective.

- J D Crossan: Jesus: a Revolutionary Biography and The Historical Jesus.

- John Dickson: A Spectator’s Guide to Jesus and Jesus: a short life. Good, simple and even-handed references by a christian historian that avoid the christian cliches and provide a good overview to what historians and christians believe about Jesus.

- Craig Evans and Tom Wright: Jesus: the final days.

- M Grant: Jesus: an historian’s review of the Gospels. I found Grant’s book readable, authoritative (he was, before he died, a respected historian of the Roman Empire, wrote more than 50 books on this period, and used the same historical methods in studying Jesus as he used in his other works) and un-biased (he was an open-minded agnostic).

- A M Hunter: The Work and Words of Jesus. Perhaps my favourite book about Jesus and the most useful reference overall – an easy to read, scholarly and inspiring summary by a Scottish theologian. Also useful are his The Parables Then and Now and Bible and Gospel.

- Prof J Meier, Notre Dame University, is quoted in M A Powell.

- M A Powell: The Jesus Debate. Powell is recognised as a fair-minded reviewer of current trends, and this book summarises the views of the most influential scholars in the field (the Jesus Seminar, J D Crossan, M Borg, E P Sanders, J Meier & N T Wright).

- Professor E P Sanders, Duke University is quoted in M A Powell.

- Prof G Stanton, Cambridge University: Message and Miracles. In M Bockmuehl.

- Prof P J Tomson, Protestant Theological Faculty, Brussels: Jesus and his Judaism. In M Bockmuehl.

- NT Wright: Simply Jesus. N T Wright is quoted in J Dickson.

Footnotes

1. Luke 11:2-4.

2. See Jesus and the Pharisees and this page.

3. Matthew 5:21-30.

4. Matthew 5:38-48.

5. Matthew 5:3, Luke 7:22, Luke 16:13.

6. Mark 2:15-17.

7. Mark 7:1-23.

8. Mark 12:28-31. Both parts of this saying can be found in the Old Testament.

9. Mark 8:29, Matthew 26:63-64, John 1:41, Acts 2:36, Acts 3:12-18, Galatians 1:1.

10. John 6:14-15.

11. Mark 1:15.

12. Luke 5:27-32, Matthew 11:28-30, Luke 7:36-50, Luke 9:23-27, Luke 18:29-30, Matthew 8:18-22.

13. Luke 11:23, John 7:40-44. John 9:35-41, John 10:19-21.

14. Luke 6:6-11, Matthew 23:23-26, Mark 7:1-23.

15. Mark 8:31-33, 10:32-34, 10:45, Isaiah 53:1-12, John 10:11-18.

16. Mark 4:26-34, Matthew 13:24-52 (“heaven” was commonly used by pious Jews to avoid saying “God”).

17. Matthew 25:31-46, John 5:22-27.

18. Matthew 11:15, 13:9, 13:43, Luke 9:59-62, Luke 12:54-56.

19. Matthew 12:8, John 13:13.

20. Luke 11:20.

21. Mark 1:29-34, Acts 10:38.

22. Mark 4:35-41, 6:35-44.

23. Mark 6:1-6.

24. John 5:1, 7:10.

25. Mark 14:36, Luke 11:2.

26. John 5:17-18.

27. Luke 23:39-43, Luke 7:36-50, Luke 23:33-34.

28. Matthew 5:25-48, Luke 6:1-5.

29. Hebrews 9:1-22.

30. Mark 2:5-7, Luke 7:48-50, John 8:1-11.

31. Matthew 23:13-14, Luke 4:18-19, Luke 5:27-32, Luke 16:15-16.

32. Matthew 12:1-8, Matthew 23:16-22.

33. Exodus 19:1-8.

34. Luke 22:14-20.

35. Luke 20:1-47, Matthew 23:1-39.

36. John 14:6, 11:25-26, 8:56-59, 8:12, 6:35.

37. Luke 22:29-30, Luke 10:22, John 10:34-39.

38. Mark 2:28, 10:45, Matthew 8:20, Daniel 7:13.

39. 1 Corinthians 15:3-7, Philippians 2:5-11.

40. Acts 2:36.

41. Galatians 1:1-3, 1:12, 6:18, Colossians 1:15-17, 2:9.

42. John 1:1-3, 20:28-31, 4:25.

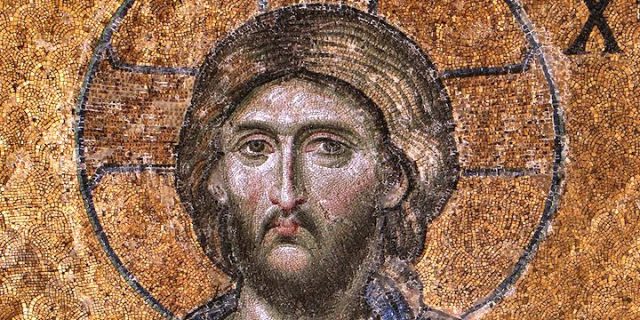

Photo: Wikipedia.

Feedback on this page

Comment on this topic or leave a note on the Guest book to let me know you’ve visited.